[Effort has been made to show more than one side of this part of history.]

The Lebensborn program was a secret SS initiative created by Heinrich Himmler in December 1935 and active until the collapse of Nazi Germany in 1945. Its stated purpose was to increase the number of children with what the Nazis considered “racially valuable” Aryan blood. The program operated in Germany and in several occupied countries, most notably Norway.

Lebensborn: The Secret Aryan Breeding Program of the Third Reich | FULL DOCUMENTARY

Join the conversation after watching this video here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AsHl8iow3OY

This summary was created by GROK, after an intense Q&A educational ‘chat’. Please do your own research.

How the Program Worked in Germany

In Germany, Lebensborn established maternity homes where unmarried women deemed to have “good Aryan” ancestry could give birth in secrecy. The SS encouraged SS men to father children even outside marriage if the mother met racial criteria. Many of these children were born to women who could not or did not want to raise them openly due to social stigma. The organization arranged for these infants to be placed with SS families or other carefully selected German couples who were screened for racial and ideological reliability. The program also expanded during the war to include the abduction of children from occupied eastern territories—primarily Poland, Ukraine, Czechoslovakia, and Slovenia—who were judged to have “Aryan” features (blond hair, blue eyes, etc.). These children were separated from their families, given new German names and identities, and placed with German families for “Germanization”.

Scale and Impact

Estimates vary because many records were destroyed in 1945. Historians generally agree that between 7,000 and 12,000 children were born in Lebensborn maternity homes in Germany and Norway. The number of kidnapped and Germanized children from eastern Europe is much higher—likely in the tens of thousands, though only a fraction were processed directly through Lebensborn facilities. After the war, many of these children grew up without knowing their true origins. Some discovered the truth only decades later through documents, family revelations, or chance encounters. A significant number faced lifelong identity confusion, shame, stigma, and psychological trauma.

Long-term Consequences

Survivors and their descendants have described deep emotional wounds: feelings of abandonment, difficulty forming attachments, bullying as “Nazi children,” and the pain of learning they had been stolen from biological families. In Norway, where the stigma against “German girls” and their children was especially harsh, many war children were institutionalized, ostracized, or subjected to abuse. Only in the 2000s did Norway formally apologize and provide limited compensation to some survivors.

This program was part of the Nazi regime’s broader racial and eugenic policies. It combined selective encouragement of births with systematic child abduction and forced assimilation. The human cost—broken families, erased identities, and lifelong suffering—is still being uncovered through survivor accounts and archival work.

Where to Learn More

- The Arolsen Archives holds digitized Lebensborn-related documents and received Dorothee Schmitz-Köster’s extensive interview collection in 2021.

https://arolsen-archives.org/en/news/85-years-of-lebensborn/ - Ingrid von Oelhafen (a kidnapped Slovenian child raised as a Lebensborn adoptee) wrote a memoir based on her 20+ year search for her origins. Book: Hitler’s Forgotten Children (2016) – available on major retailers

(e.g., https://www.amazon.com/Hitlers-Forgotten-Children-Lebensborn-Identity/dp/0425283321) - Dorothee Schmitz-Köster conducted hundreds of interviews with Lebensborn mothers and children over more than 25 years. Her books include: Deutsche Mutter, bist du bereit … (2002/updated editions) Lebenslang Lebensborn (2007)

Her website: https://www.schmitz-koester.de/ - Documentary: Lebensborn – The Forgotten Victims (2019, ~53 min) includes testimonies from former children in multiple countries. Free with ads on Tubi (US- may need a VPN set to US to view):

https://tubitv.com/movies/640639/lebensborn-the-forgotten-victims

This is an interview from January 1988 with Ilse, a Lebensborn nurse in Steinhöring, Germany from 1936 to 1945

(Original document below; translation provided by grok.)

Page 1

I wanted to ask you some questions about your service in the Lebensborn association and about all the myths that surround this idea. Would you tell me how you came to Lebensborn?

Ilse: Yes, I am happy to answer your questions, and I trust that you will ask some good ones. I look forward to dispelling many of the false stories about Lebensborn, which was created by RFSS (Reichsführer-SS) Himmler. I will begin by telling you my story. I attended school in Munich and first heard of Hitler and the National Socialist Party in 1925, when I was 10 years old. My parents began to take an interest in political events, and so did I. I joined the BDM (Bund Deutscher Mädel [League of German Girls]) and became a member of the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei [National Socialist German Workers’ Party]) in 1933.

In 1935 I attended nursing school and met my future husband, who worked in the RuSHA (Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt [Race and Settlement Main Office]). He was involved in family welfare and dealt with all the problems that SS men had in relationships, marriage, and marital issues, including child-related matters. Since my husband was close to Himmler and Max Sollmann, I was asked, after becoming a nurse, to work in a new enterprise that was being founded to help SS families who were expecting a child.

I was assigned to the staff of the Lebensborn home in Steinhöring, which consisted of about 30 specialists and nurses from all medical fields. To be accepted into the staff, one had to be appointed by the RFSS after passing a strict examination proving that one had no conflicts with the police and was not mentally unstable. In addition, one had to be a member of the SS, and I had to prove my racial purity.

May I ask you what this “racial purity” was about? That is something our schoolbooks and media mock, telling us it was typical vulgar Nazism and a myth.

Ilse: Well, the world’s media are to this day in the hands of precisely the people we tried to expose and remove from influential positions. For them, race plays no role; it is a man-made creation that divides and creates boundaries. They are a people without borders and are waging a hidden war against the European people to destroy what binds us in a common bond.

In Germany, they promoted the destruction of races by bringing Africans, Indians, and Orientals into the country to mix with German women who were depressed and desperate because they had lost their spouses in the first war. RFSS Himmler was not the first to draw the masses’ attention to racial consciousness; he was the first who had the means to put it into practice.

What I mean is that the first war decimated Europe’s gene pool; some of the best men fell, many without having children. One of the NSDAP’s first tasks was to rebuild the family, to enable a man and a woman to be happy and debt-free so they could have as many children as possible to make the nation grow. One task was to ensure that Germany had German children who would carry on the culture of their ancestors. These ancestors were Aryan, which is a general term for white but specifically refers to light skin, eyes, and hair. The RFSS believed that this type was the purer form of the white race that God had created from the beginning. Only through racial mixing did darker traits creep into the bloodlines of European peoples.

Page 2

This happened during various conquests and invasions in our long history. When the Jew came to Europe 700 years earlier, the intermingling of Aryans and Jews began. Some Jews desperately wanted to look like the people among whom they lived, others adhered to strict marriage rules, and still others wanted to become as Aryan as possible while remaining Jews. This class was more interested in money and power than in preserving their Ashkenazi appearance.

Over several decades, many Germans fell victim to the advances and power of these foreigners. The NS view is that no one has the right to impose their will on the people if they do not come from the people. The Jews in Germany were a tiny minority but owned a disproportionately large share of businesses and wealth, so their will could be enforced unhindered. They used this wealth and power to divide and destroy the morals and structure that our faith, history, and culture had built. For this reason, they are seen as an internal enemy who cannot be trusted and will never be German.

The SS was created so that Germans could return to the traditions of our ancestors and preserve the culture we had inherited. Anyone who wanted to join the SS had to prove that there had been no racial mixing in their bloodline for at least 200 years. This was to exclude all Germans who had blood from non-whites who had been brought to Germany, including Jews.

The RFSS once gave a speech in which he said “that it should always be the goal of every person on earth for their children to look like themselves, to carry on the culture into which they were born.” That is what racial purity is about: preserving what exists. We dedicated ourselves to this idea.

Thank you. Can you tell me what life was like in the home?

Ilse: Yes. The Lebensborn homes were established so that German women who had become pregnant could come and be cared for around the clock. This included married wives of SS officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers; there was no class structure in the SS like in old aristocratic Germany. All were equal and deserved love and respect.

Our homes were like a resort; the food was good and there was a very relaxed atmosphere. We also allowed this for women who were not married. This caused us problems with those who looked down on girls who became pregnant unmarried. Soldiers are soldiers; they have male needs, and there are women who give in to those needs, which can sometimes have unwanted consequences.

Abortion was a social norm in Germany before the NS; everyone was encouraged to be immoral, and if the worst happened, one simply undid one’s mistake. Under NS rule, a woman could only have an abortion if it was determined that the child was damaged or the mother’s life was in danger. SS men who impregnated a girl were ordered to the RuSHA for a formal investigation into their intentions to stay with her. If she wanted to escape disapproving parents or family, she was welcome in our home.

Page 3

Regardless of whether a woman was married or single, she was welcomed and well cared for. The youth organizations tried to teach our youth sexual morals to curb unmarried pregnancies, but the morals of the Weimar era were still noticeable in some of our people, even in the SS. It is not true that young, unmarried girls were encouraged to have sex and bear a child for the Führer; that is enemy propaganda.

Until the start of the war, most of our patrons were married women who just wanted to be pampered for a few months. SS officers paid monthly to allow their wives this privilege and unique experience.

When a woman arrived, she was given a room to live in, similar to a hotel. She was examined by doctors who assessed her health and looked for any risks. Married women came to the homes because they might feel lonely while their husbands were away or simply wanted to be among other SS women with whom they shared a bond. Unmarried mothers were often on their own for the first time and afraid; the homes offered expert care and a relaxing environment. There, the expectant mothers were waited on hand and foot, and everything was paid for by the SS.

Courses were held for first-time mothers to promote natural maternal instincts. Each course was designed to build confidence and remove fear of giving birth to a child. Men could also attend courses for new fathers, and there were counselors for all relationship issues. Women often struggled with stressed and abusive husbands. This caused chaos in the family and frightened the children. The SS was very proactive in ensuring that all stress factors were eliminated. A happy family is a productive and fertile family. Financial worries were eliminated, health care was free, there were plenty of jobs, and there was hope for the future. There were virtually no cases of spousal abuse or harm, and the RuSHA investigated all allegations and could refer them to a court of honor. I think I saw only one case where an SS officer abused his wife, and he was a drunkard and was expelled from the SS. His wife was protected and received a divorce. After the birth, she stayed with us for a few months.

An expectant mother was encouraged to follow an exercise program, go outdoors daily, take sunbaths, eat healthily, and meditate to prepare her mind and body for birth. When the time came, she gave birth to her child with the help of SS doctors and staff, and then the homes took on the form for which they were intended. The newborn was cared for around the clock by qualified staff. Any illness detected was treated quickly. The nurses took the child daily to give the mother a break, so that if she wanted, she could go away for a while. These homes were created to take away all the stress and worries before, during, and after birth. Mother and child could stay as long as they wanted, but most preferred to go home a few weeks after the birth.

Why is this program so misunderstood? I was taught that girls were forced by paid SS officers to go to these homes to become pregnant.

Ilse: Ha ha, I sometimes still laugh at the ignorant propaganda that our enemies spread without really accepting what we told them we did. The truth is the first casualty of war; you want your people to feel good about what they…

Page 4

…for what they are fighting. This includes making the enemy appear evil, with evil intentions. The Allies were and still are masters of the propaganda war. They easily won this war. NS-Germany was a state of the first rank, and the Allies were very envious of what we had achieved, so they went to war to prevent us from gaining more influence on the continent.

In 1945, I was still in the home in Steinhöring, but I had been promoted to other tasks, including to other homes in Europe. Therefore, I knew what was happening in Norway, France, and Poland.

The first contact with the enemy was that US officers came to our home because someone had told them we were a brothel for SS men. Our home director explained to them that we were a children’s home and urgently needed food and supplies. They left and came back quite quickly; I have the feeling that they saw the pretty nurses as tempting targets, as they also brought wine. They were quite curious why a local had told them we were a brothel. When they learned that we belonged to the SS, they went completely crazy from the stories they had heard from the ranks of the SS. I had learned English in school, like many Germans, so I could talk to them a little, and an doctor and I tried to explain that this was a children’s home. The Red Cross was brought in to ensure the supply of food and medicine.

Then the interrogations began; Lebensborn was accused of kidnapping children and euthanasia. People came forward who accused us of all sorts of crimes; fortunately, the usually vengeful Allies found no evidence to confirm the claims.

By the way, how did the average German perceive Lebensborn?

Ilse: Most Germans knew nothing about us, but those who lived near the homes were naturally curious. In Steinhöring, we had many visits from officers, high party officials, and foreign dignitaries. It was a special pilot project of the RFSS (Reichsführer-SS) and this model was seen as a future service for all. Since it was a home financed by the SS, we occasionally received requests from local churches to take in a pregnant girl who did not know the father, etc. They were advised to turn to other NS welfare organizations. This led to a certain contempt, as we were seen as elitist and insensitive, but that was only for SS members, similar to a private spa resort. However, there were also times when we had to help in emergencies. We had a woman who was in labor and lived nearby. She was brought to us, and our staff delivered her baby and cared for her. We never turned away anyone who was in an emergency and needed immediate help.

Unfortunately, after the war, many Germans—for reasons I do not fully understand—said the most vile things about us and the children we cared for. I suspect that many of the rumors about stud farms and forced breeding camps come from this. There were many ex-communists who still lived in NS-Germany, and I believe they were given special platforms to tell their side of the story, as a communist would like it. And being a victim was fashionable after the war; everyone was an NS victim.

Page 5

What was it like during the war?

Ilse: The war brought many changes for us. A major change was that we became nurseries for SS (Schutzstaffel) mothers who needed a place to look after their babies while they fulfilled their duties and worked. Our staff was expanded to accommodate all military pregnant women, whether SS or not.

The RuSHA (Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt [Race and Settlement Main Office]) began opening further homes across Europe, as SS men had relationships with foreign women. This was very common in France and Norway. Our strict racial standards were even bent to a certain degree, as the main goal was to give soldiers—who might never return—the opportunity to pass on their seed. In most cases in the occupied territories, it was simply about safety, so that a woman in love with a German could have her child without being condemned or threatened. There was more than one case where a woman and her child were murdered just because the father was German.

I want to talk about one thing for which we were held responsible, but which was in reality a good deed. Due to Allied bombing raids in the occupied territories, parents who: no longer wanted a child, arrests, illnesses, and deaths, a child was brought to Lebensborn to be placed in a suitable family for adoption. Our enemies had great success with this. We never stole or kidnapped children, and if a child was forcibly taken, it was only because of a crime or neglect, and that was rare. In contrast to what the victors say.

I was temporarily tasked with examining children coming from the East who were to be released for adoption, and the story was always the same. The parents abandoned the child, died, or were ill and had no other relatives to take them in, or they were war victims. This was later a big problem in Russia, as the NKVD/the partisans killed entire families but did not find the hidden children.

There were a few cases where a child was forcibly removed due to abuse or severe malnutrition. In such cases, the NS welfare authorities tried to place the child in another family, and if none could be found, it could be released for adoption.

How many children, do you think, survived the war?

Ilse: I can only guess, but there must have been hundreds; it didn’t seem like a large number, and there were other German organizations like the Red Cross that tried to help anyone who could not be reunited with their family, but in wartime that was not always possible. I believe some of the “kidnappings” were situations where the family fled with the Red Army, became separated, and the child ended up with us. After the war, the family searched, and of course the enemy stole the child.

We were a welfare organization and only wanted to help people, not cause suffering. So remember: Truth is the first casualty of war.

In Norway, many children were born to women who had relationships with German soldiers. Our home was open to everyone there, not just SS units. The women were brought here to protect them from malicious neighbors and the resistance. They were innocent children, but at the end of the war they were forced to leave the country in which they were born.

The Left invented the same old stories about SS breeding camps and stigmatized these children as some kind of mutants. Denmark did the same. Many of these children died because of this hatred, and that is covered up to this day.

Page 6

German soldiers harbored no hatred toward the people in the countries they were forced to occupy, and of course the women were curious about what this enemy looked like. German personnel were encouraged to go out and meet the population to let them know that they wished no one harm. Good friendships were formed, and as a result there were many pregnancies. Since abortions were forbidden, the women had to bear this burden—unless the pregnancy threatened the mother or child. Our homes were the perfect place where they could be pampered for a few months. Even foreign workers who volunteered in the hundreds of thousands were accommodated in our homes during the war.

What began as homes for SS women and girlfriends became refuges for people with children trying to survive a terrible war.

Can you tell me what it was like for you after the war?

Ilse: It was terrible and frightening. My husband remained in the RuSHA staff throughout the war; he was in a key position responsible for the welfare of soldiers’ families and therefore not conscripted. He was often in Berlin, and I preferred to stay in Munich, so we often did not see each other for weeks. We tried to have a child, as was our duty, but it did not succeed until 1948.

He was able to leave Berlin with orders to come to Munich and was then captured by the Americans under General Patton. After a few months he was released, and we were reunited. I was mostly left alone but was often harassed by Allied soldiers demanding sex. I made sure never to walk alone and was in constant fear of being assaulted.

The home in Steinhöring remained open after the war, but the Red Cross and Allied medical personnel now controlled the home. Most of us were allowed to stay with the remaining children; others were asked to go to nearby hospitals that were not destroyed. The home was eventually evacuated and closed; I had already left it and was asked to join the staff of a private hospital in Munich; my husband was brought into a business by an old comrade.

I was sad when I learned of the terrible fate of many children born in our homes. They bore no guilt, yet hypocritical people who could not overcome their petty differences to care for children treated them as defective or immoral. In the 1950s I got into trouble when everyone associated with Lebensborn was sought to answer for kidnapping. I vigorously rejected the accusations and defended our mission, which drew attention to me as I called the Allies liars and true war criminals. The occupation government did not like that and threatened me with prison, so I have largely remained silent all these years, because my family and my children deserve a mother.

In retrospect, the Lebensborn program was revolutionary, as it offered women a safe, comfortable, and supportive place to have a child with the best care. I can testify that it was not an SS “sex farm” as our media reported; we only wanted to care for those who were to bear the future of our people.

Dies ist ein Interview vom Januar 1988 mit Ilse, Lebensborn-Schwester in Steinhoring, Deutschland von 1936 bis 1945

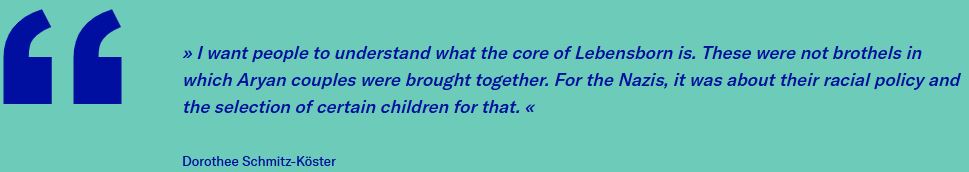

Dorothee Schmitz-Köster began researching Lebensborn back in the mid-1990s

– initially focusing on the “Friesland” home near Bremen, where she lived at the time. She soon expanded her search to other homes, as more former Lebensborn children got in touch with her with information as well as many questions about their own past after each publication. Her research took her as far as Poland. The author thus became an expert in the history of Lebensborn. She published four books and created many radio and print contributions about everyday life in the homes and the lives of many children.

In this video interview [Video was removed from the page and not found, link to source below.], we ask Dorothee Schmitz-Köster about her experiences during the Lebensborn research and about her decision to hand over her collection to the Arolsen Archives.

Dorothee Schmitz-Köster always wanted to collect as much material as possible in her research so as to record the voices and stories of the contemporary witnesses – who are becoming fewer and fewer in number. Alongside a good overview of the many different individual fates, it was also important to her to clear up the myths and rumours surrounding Lebensborn as a “breeding institution”

Predominantly single women were to deliver their children in the homes, as long as they and the father – who were often married SS men – fulfilled the racial criteria. The mothers could also remain anonymous and give their babies into the care of Lebensborn, which then sought an “Aryan” foster family. Many of the babies never discovered the truth about where they came from. This also applied to many “Aryan” children abducted in Poland and other occupied countries in order to “Germanize” them.

https://arolsen-archives.org/en/news/85-years-of-lebensborn

Independent Film: Snatched from the source / A film about four people, who were stolen as babies in Slovenia

The film has so far been shown in Germany only twice: at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2023 (when Slovenia was the guest country) and in December 2024 in Berlin, as part of the Slovenian Film Days. Otherwise, nothing… No interest? Not suitable for the public? Or simply ignorance? In any case, it is certainly not due to the quality of the film!

Director Maja Weiss tells a story that is hardly known in Germany.

She tells of child abductions in Slovenia, using the example of four biographies to show what happened to the 645 Slovenian stolen children. When the German National Socialists occupied the country and tried to break the population’s resistance with so-called “retaliatory actions” – against entire villages, against the old and the young, against fathers, mothers, and children. On 10 August 1942, the four protagonists of the film were separated from their families and taken away to a camp. At that time, they were three months, five months, nine months, and 15 months old. After several stations and “racial” examinations, they ended up in the Lebensborn home in Kohren-Sahlis (near Leipzig). In the eyes of the National Socialists, they and 26 other Slovenian children were “good enough” for the Lebensborn project, “good enough” to become good Germans. A short time later, couples came to the home to adopt an “Aryan” child. At the latest now, the boys’ and girls’ names were changed – and the remaining information about their origins was erased. Vili Goručan became Haymo Heinrich Heyder, Erika Matko became Ingrid von Oelhafen, Franc Zagožen became Franz Chantrain, and Ivan Acman became Hans Friedrich Ritter von Mann Edler von Tiechler.

Read more https://schmitz-koester.de/virthos/virthos.php?//Lebensborn-Blog/Slowenischer%20Raubkinder-Film

Snatched From The Source https://belafilm.si/en/seznam-filmi/snatched-from-the-source/

Example of the type of information that can be found at the Arolsen-Archives

Content: Classification stamp (top): DECLASSIFIED PER EXECUTIVE ORDER 12356, SECTION 3.3, NND PROJECT

NUMBER 86077-3051, BY [signature], DATE [illegible] Main body text: OFFICE OF THE FIELD REPRESENTATIVE FOR BAVARIA

INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE ORGANIZATION

AREA 7 HQ | APO 407

US ARMY 24 January 1949 TO : Miss Josephine GROVES,

OMGUS Public Welfare Branch, 210 Tegernseer Landstrasse, MUNICH

SUBJECT : Children removed from Geratshausen

- This will confirm the report from our Area 4 Head-quarters, Gauting, that the following children were removed from Geratshausen to the Children’s Village in Bad Aibling on 20 January 1949:

GALUSCHKA, Gerhardt, b. 21.2.42

JARUS, George, b. 26.6.42

LUBRA NIEWIADOMSKI, b. 6.4.39

[Signature]

Marjorie M. Parley

Child Care Field Representative

Munich Distribution:

(4) Addressee

(1) Zone Child Care Officer

(1) File

(1) Chron

Information on the Children’s Village in Bad Aibling

Höschler, Christian (2017): The IRO Children’s Village Bad Aibling: a refuge in the American Zone of Germany, 1948–1951. Dissertation, LMU München: Faculty of History and the Arts

Abstract

Based on a variety of source material and previous research, this microhistorical study represents the first comprehensive history of the IRO Children’s Village Bad Aibling. Established in late 1948, it was the central facility within the US Zone of Germany where unaccompanied children were cared for by the International Refugee Organization (IRO). Displaced during or after World War II, their fates were as varied as those of adults who had survived the atrocities of the Nazi regime. In total, over 2,000 children (representing more than 20 nationalities) passed through the Children’s Village.

The early days were marked by a prolonged struggle to get the installation into running order, secure necessary supplies and hire qualified staff. Tensions which arose as a result of these problems culminated in violent episodes of unrest among the children. The administrative setup in Bad Aibling was reorganized, and the situation gradually improved.

With the help of various voluntary agencies such as the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), an ambitious program was developed from 1949 onwards. It was inspired by contemporary trends in child welfare and aimed at developing an inclusive, international community consisting of family-like living groups. Through schooling and vocational training, recreational activities, psychological treatment and individual case work, the inhabitants were prepared for life after the Children’s Village. A decision regarding the future of each child had to be reached. In the majority of cases, the options were either repatriation or resettlement abroad. While the political friction of the Cold War had an undeniable effect on the IRO’s activities in Bad Aibling, it seems impossible to derive a universal set of beliefs guiding the work of relief workers from this fact. Despite occasional contact with the German population as well as international press coverage, the Children’s Village remained more or less isolated from the outside world.

The last months of the Children’s Village saw new challenges as the IRO slowly began to wind down its operations in Europe. A change in US occupation policy saw the introduction of new courts which would decide the cases of the remaining children. In 1951, the Children’s Village shut its doors, and its inhabitants were moved to Feldafing. By early 1952, the cases of the remaining children had been closed.

It is believed that the history of the Children’s Village, as part of a broader narrative of humanitarian efforts and child welfare in the postwar period, is relevant to the sphere of international relief work today.

Shared from https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/20571/

CASE No. 73

TRIAL OF ULRICH GREIFELT AND OTHERS

UNITED STATES MILITARY TRIBUNAL, NUREMBERG,

IOth OCTOBER, 1947–1Oth MARCH, 1948

Criminal nature of racial persecutions-Genocide-Membership of Criminal Organisations-Plea concerning annexed territory.

Find more from the World Court: https://www.worldcourts.com/imt/eng/